Brand Transformation: A New Approach in the Digital Age

While auto manufacturing techniques are far more advanced today than when Henry Ford opened his first factory a century ago, one thing has remained consistent over time: the assembly line. What’s different today are the components of the assembly line itself: from humans to hardware, and increasingly today, software. The average car today has more computing power than the system that guided the Apollo astronauts to the moon. This astounding reality has largely underpinned the revolution we’ve witnessed in the auto industry — from vehicle-based hardware to software-based mobility.

Just as the methods utilized to build cars has been modernized, it’s time we updated how we transform brands as well. The legacy constructs of visual and verbal expressions of a brand, coherently organized into a consistent and distinctive system, are overdue for a refresh in today’s digital context, where digital is changing what a brand looks and sounds like, as well as how it behaves —and what it can do.

How is brand transformation accomplished? Let’s first take a deeper look first at why it’s imperative, then look at the new approach and tools necessary in this time of digital disruption.

Why is Brand Transformation Necessary?

Codified in guidelines, protected by marketing departments, adopted by employees, obeyed by vendors and absorbed by customers — for more than 150 years, traditional brand identity has been painstakingly crafted and translated into an elegant, fixed systems of architecture, pillars, visual-verbal elements and more. And it worked. This exhaustive and storied approach has helped countless brands from AT&T to Zurich successfully navigate, endure and grow with consistency through decades of customer evolutions and media revolutions.

But today’s increasingly digital world demands new ways to build and manage brands. The next wave of growth for brand looks different in a world where brand is experienced through platforms and ecosystems other than its own; where touchpoints and channels multiply daily; where interfaces become invisible; where machines are increasingly responsible for deciding preference. In this new ecosystem of data, algorithm and context, what is the role of brand? And more importantly, how do we build and manage a brand in this new paradigm?

In this disruptive, digital era of customer empowerment and interactivity, brands are now growing better when they are built to be relentlessly relevant to their consumers and against their competitors.

Brand Operating System: A New Approach to Brand Transformation

To deliver relentless relevance, brands require new levels of organizational readiness and responsiveness than ever before. Rapid cycle times driven by prototyping and ongoing releases mean relevance has an ever-shrinking shelf life. Stickier networks and ecosystems make it harder to win over consumers who reside elsewhere. Participatory experiences require brands to think in terms of relevant creation—and reaction. Massive sources of data offer endless opportunities for insight.

“Today’s increasingly digital world demands new ways to build and manage brands.”

These changes call for a new approach — from a static, two-dimensional system (preserved in a PDF) to a dynamic system that connects brand across and between experiences and ecosystems, versus just across physical spaces: A Brand Operating System (BOS). A system encompassing the tools, policies and processes that create the internal infrastructure needed to develop and deliver responsive, adaptive and intelligent brand behaviors and experiences in market.

The strategic and operational challenge is that a BOS is not static. However, most companies are not yet set up to deliver in this way, still approaching brand via PDF toolkits, guidelines, siloed asset management systems and siloed governance.

How to Transform a Brand in Light of Digital Disruption

Here are three ways to transform a brand and build brand relevance:

1) Leverage New Tools

The static, inflexible, PDF guidelines of the past are insufficient. Their contents — visual, verbal and spatial considerations — still remain integral ingredients, but they must be updated for digital applications and platforms. Managing brand across new digital spaces requires new platform integrations, content and asset management systems, dashboards and tools that help you design, maintain and deploy brands in these new environments. Your message pillars, for example, can’t be rigid. Say a new and relevant conversation is heated in the social space, a brand manager needs a flexible language platform from which (s)he can adapt or even add a pillar to recognize the current conversation. Retail environments are shifting rapidly, requiring imaginative ways to express brand in spaces as screens, beacons, biometrics and NFC proliferate. Flexible brand assets are key to staying relevant.

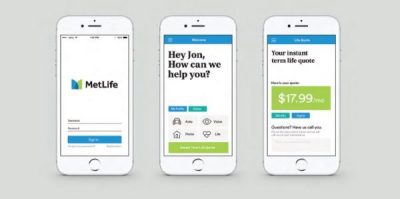

Furthermore, a BOS requires entirely new ingredients, namely around behavioral guidelines that assert how the brand behaves and engages. For example, a chatbot assisting customers on a brand’s site must not only take on the brand’s tone of voice but be programmed to dynamically respond to questions and queries for each unique question — and get smarter from each question asked.

That classic PDF thus becomes an inadequate format for the Brand Operating System. As a fluid system, the BOS must be able to allow for new elements to be added all the time in order to allow it to be responsive to the world in which it operates. The most precious asset thus becomes not a PDF, but a set of platforms, code, tools and ways of working, like software, that enables regular updates.

2) Brand Defines the Means Not the Motives

There’s a need to broaden the definition of brand from an articulation of a company’s motives and ambitions towards an actionable policy that concretely guides decision-making internally to shape (data-driven) behaviors. A tangible and directional positioning enables front-line/customer-facing employees (e.g. customer service, sales) to have more concrete direction on how to behave. For example, Coca Cola’s positioning of “happiness within arm’s reach” sends a clear signal to salespeople about where the product needs to be (within arm’s reach); Disney’s positioning of “magic” translates concretely into quality standards that direct specific employee behavior: courtesy (smile), safety (seat belt checks), efficiency (fast service) and show (costumes).

Means vs. motives also inform the specific code and command engineers and data scientists use to program-specific branded triggers and behaviors. With a means vs. motives approach, digital and other “behavioral” teams (engineers, data scientists, designers, customer service, sales and other front-line roles) have a more concrete point around which to activate the brand. Looking at Coke again, “within arm’s reach” a UX designer translates that brand policy to inform the information architecture of the site, or where buy buttons are placed (within a click’s reach).

3) Embrace New Brand Stakeholders

To deliver on these new touchpoints and enablers, companies must broaden the skillsets they hire for — beyond marketers, brand managers and communications planners to UX/UI interaction designers, front-end and mobile engineers, MarTech and full-stack architects, scrum masters, DevOps and systems architects, to name a few. This has implications for where you look — Glassdoor, Hacker News, StackOverflow and social media become new networks to leverage — as well as how you look. UPS, for example, shifted from 90% print budget in 2005 to 97% in social media in 2010. The result was better quality hires — the interview/hire ratio was 2:1 for applications from Facebook and Twitter compared to all other media — and a reduction in overall costs, with the cost of a new hire going from $600/700 to $60/70 each.

These new skill sets enable companies to in-source a greater number of activities that were either previously managed by agencies, or simply did not exist, in order to better control and execute the brand behaviors and experiences. An in-sourcing approach is not at the expense of outsourcing — agency support is still valuable for production and other intermittent campaigns — however, the presence of new skill sets now creates the mechanisms needed to be more agile and facile with how agencies are briefed and managed.

Cultivate Flexibility and Create New Partnerships

Increasingly, the people, processes and structures that enable relevant brand behaviors matter as much as the brand design and positioning itself. This extends beyond developing a brand management framework and instead calls for a detailed governance model that creates the skills and culture needed for a flexible, always upgrading approach to manage and activate the Brand Operating System.

For example, Buzzfeed editors are paired up with data scientists to make data-driven decisions about their editorial approach. By tracking cookies, pixels and IP addresses, Buzzfeed can understand not just individual preferences (and in turn personalize your experience), but it can better understand “clusters,” which may reveal that a population’s interest in a celebrity actress also correlates with their interest in content about a cute animal. Editors on their own wouldn’t produce this knowledge; it’s the combination of traditional (editors) and new (data scientists) that lead to powerful insights to power relevant content, and thus grow the business.

How to Get Started on Transforming Your Brand

Here are the key questions to ask as companies begin to think about the Brand Operating System approach:

- As the brand, do we have the right tools in our toolkit?

- Is there access to the right technologies and tools to capture what’s necessary to deliver on behavioral brand?

- Is brand set up in a flexible way to modify to allow for pivots as consumer and competitor dynamics shift?

- Are the right tools in place to handle these shifts?

- Where can we add agility to our brand and empower employees?

- Are the right agile approaches embedded into key points where it matters most (e.g. product and service innovation, marketing, customer service, etc.)?

- Where else can these principles be used throughout the company to enhance relevance?

- Are the right incentives institutionalized to encourage new behaviors across the employee base?

- Do we have the right organization and people in place?

- Is the company organized internally to align the different parts of the brand’s ecosystem with more points of integration (e.g., suppliers, partners, vendors, consumers)?

- Do employees have the right skillsets and capabilities to deliver the brand and relevant experiences?

- Are they organized and empowered to be stewards of brand and experience via the right governance structures?