BLOG

Five Rules for Optimizing Omni-channel Clinical Care Models

Building a human-centric healthcare organization that delivers on patients’ needs.

With the pandemic increasingly in the rearview mirror, many healthcare organizations are coming to terms with the big and small changes that have become permanent parts of the healthcare landscape. Ushered in during the pandemic, omnichannel care delivery is now a fixture and will play an influential role for many years to come; that’s a good thing, as patients prefer having options and are often enthusiastic about new channels, technologies and treatments. More caregivers now see the value of omnichannel care, especially telehealth and in-home care, because they work so well for patients.

In our recent work with clients, we’ve seen how different types of healthcare organizations can capitalize on leading practices for change and transformation as they seek to refine, optimize and expand their omnichannel clinical care models.

The common denominator with healthcare leaders is human centricity. Organizations that successfully drive change design their care models around what patients want and need. Similarly, organizations that adopt a human-centered approach to transformation are more likely to succeed in winning hearts and minds, instilling new behaviors and changing the culture in sustainable ways.

1. When transforming the clinical care model, start small and iterate fast.

There are ample transformation opportunities across healthcare but organizations that take on too much change too fast are bound to struggle. The key is to focus on the achievable while understanding the distinct needs of underserved populations and addressing drivers of high cost.

Organizing around a condition or a use case, rather than a service line, can be useful both for making progress and setting up for broader change over the long term. Breaking down big changes into manageable steps is the only way to go. For example, to redesign diabetes care, leaders will need first to address issues typically treated by primary care, endocrinologists and cardiologists, as well as supporting clinicians in nutrition and other related aspects of care.

Our work with one national player confirmed how many patients with kidney failure “crash” into dialysis in an unplanned fashion when longitudinal care models can address the holistic needs of such patients. When Geisinger launched a home care program, it realized impressive results, including reduced ER visits and lower costs, largely due to its careful patient selection, a focus on chronic conditions and proactive outreach by care teams.

Within value-based care models, better patient communication can increase HCAHPS scores, which directly impacts reimbursement. That’s a relatively small-bore change that can yield potentially big results.

2. Recognize that every healthcare organization is also a software company. And an AI and data science firm, too.

Whether or not they want to be, all types of healthcare companies are in the technology business – and we’re not referring exclusively to electronic medical records (EMRs). Software now underpins every step of the care delivery process and is essential to making the “anytime care from anywhere” vision a workable operational reality. And yet, there’s no denying that tech has contributed to significant burnout among healthcare workers, including physicians.

Healthcare organizations would benefit from several tech innovations, including agile sprints and experience design principles, to continuously enhance features. Had EMRs been designed in this manner, they would more seamlessly fit into the clinical workflow and not contribute to provider burnout as they are today. Healthcare organizations can take a similar approach as they design omnichannel care delivery models and deploy new technology.

Thinking like a service designer will help orchestrate the linkages between backstage systems and data sources and, ultimately, create a seamless experience for all types of users. Accommodating the needs of users with different levels of technology access and literacy – including both patients and caregivers – is the key to developing high-impact solutions. When designing a patient app for patients receiving home dialysis, we went through multiple rounds of design and user testing to ensure that the experience met patient needs in an intuitive way and delivered the right information at the right time. That’s how to empower – rather than overwhelm – users.

Organizations must also change the perception, common after initial rollouts of EMR systems, that technology is the enemy. One way to overcome that persistent bias is to co-create solutions with patients, caregivers and providers. That’s what we did with a national player seeking to shift the site of care from clinics and inpatient settings to the home. Service designers worked directly with nurses and nurse practitioners who could speak empathetically to the day-to-day needs and challenges faced by home healthcare teams and provide feedback on initial design sketches. These foundational insights, as well as those from patient groups, guided the design of new tools.

AI Goes Everywhere

There’s no talking about tech without talking about artificial intelligence (AI). AI seems to be taking over healthcare. Payers are using it to digitize claims, conduct audits and monitor payments. Clinically, AI is helping physicians scan X-rays and get ahead of emerging risks and adverse outcomes. Providers use AI to design care paths, personalize care coordination and model the financial impacts of different treatment plans. AI promises to revolutionize clinical trials in the pharmaceutical sector.

Embedding AI-enabled technology deeply into care delivery processes can make routine tasks simpler, faster and safer. And it’s the most effective way to use technology as a “force multiplier” in delivering care, which is the primary motivation for many healthcare organizations that acquire technology companies. Technology that enables caregivers to do their jobs more effectively and operate at the top of their licenses is invaluable in a time of provider shortages. Equipping end-users (including physicians) with training, skills and knowledge to use the right tech at the right time is how tech can directly support better outcomes.

That sort of human-centered approach is necessary to change minds, create advocates and smooth the transition as the organization evolves from being healthcare-centric to thinking and acting like tech, AI and data science companies.

3. Transformation takes an ecosystem.

Achieving ambitious change objectives will almost certainly require collaboration with others – including payers, specialty care providers, technology companies or other third parties. So finding the right partners is critical, even when focusing on a manageable, well-defined issue or opportunity.

The massive complexity of healthcare – both as a business and in terms of delivering care – makes broad organizational buy-in an absolute imperative for effective transformation. Overlooking a key constituency can make the difference between success and failure.

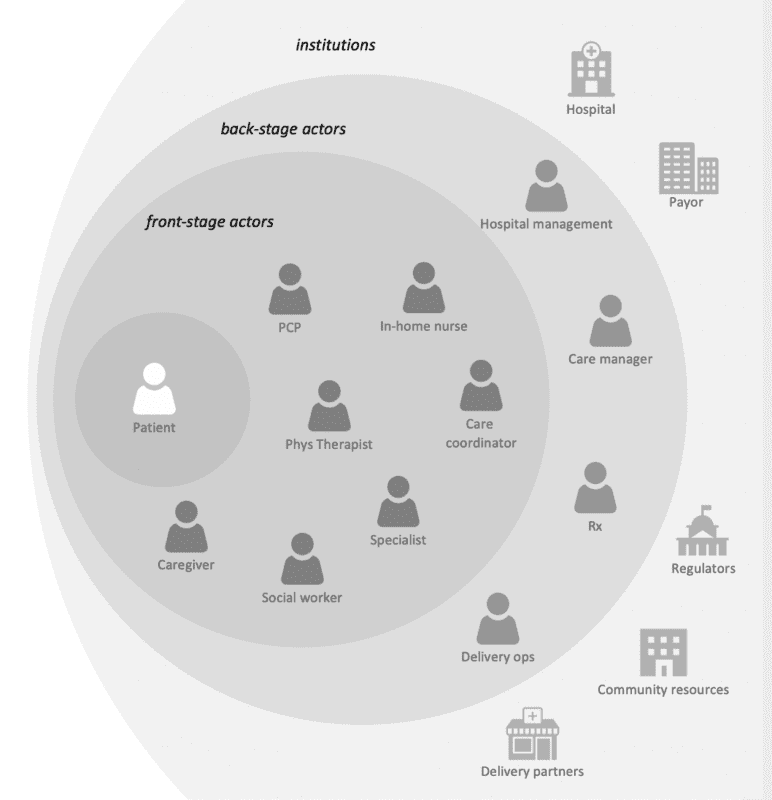

We define stakeholders as anyone playing a role in care or invested in its outcomes. Thus, the universe of stakeholders includes everyone from institutions (e.g., payers and large employers) to back-stage actors (e.g., hospital management, pharmacies) to front-line care providers (e.g., PCPs, specialists, therapists, care coordinators, social workers) and, of course, patients who must remain at the center. These stakeholders have wildly different incentives, hold different values and operate with different information and authority.

The broadest ecosystems require teams to think like systems designers in working outward from the patient to the entire stakeholder ecosystem, including front-stage actors (e.g., caregivers, PCPs and specialists) and back-stage actors (e.g., care managers, pharmacists, hospitals, payers, regulators).

Ecosystem design requires incorporating the needs and perspectives of many different stakeholders.

All of these players have widely different incentives, hold different values and operate with different information and authority. Misalignment among ecosystem partners can manifest in systemic problems that reach deeper than any single touchpoint. When we design healthcare ecosystems, we apply such principles to understand current systems and envision those that will be necessary tomorrow. Design tools such as ecosystem and value exchange mapping are a critical part of incorporating the entire innovation ecosystem into specific solutions.

Leveraging Internal Ecosystems

The most successful transformation programs also involve many different internal constituencies. One Fortune 500 healthcare organization seeking to disrupt renal care with increased use of in-home dialysis built a diverse, cross-functional team, including digital strategists, product teams, client nurses, nephrologists and other specialists, in its ideation process. It gathered ongoing input via iterative design and feedback sessions. The testing process of initial solutions involved 40+ external users, including patients, nurses and other caregivers and social workers.

Organizations enacting large-scale strategic change often convene a leadership council for regular reviews and feedback. Typically, such groups include chief medical officers, clinical business unit leaders, medical specialists and senior operational and administrative leaders.

4. Embrace regulation and payer mandates as inspiration for innovation.

The expanding adoption of value-based care shows how regulatory requirements can prompt necessary change for organizations with creative leadership and high degrees of operational agility. By default, many leaders resist new rules and love to complain about old ones, which can lead to regulatory oversight being used as an excuse not to change.

Federal regulators are certainly looking to foster innovation and prompt greater use of in-home dialysis via reimbursement changes in kidney care and other areas. The acute shortage of clinicians is another area where regulators are likely to be flexible in allowing healthcare organizations to experiment with new care delivery options. Consider how pandemic-era stop-gap measures to allow providers to practice telemedicine across state lines have remained in place. We believe the clinician shortage is an existential threat that must be at the forefront of the design of omnichannel care delivery models. Certainly, it will force provider organizations to automate more low-value tasks as they seek to expand their reach.

Social determinants of health (SDoH) are also being incorporated into regulatory frameworks as their importance to health becomes clearer. Medicaid changes are more likely in the short term, with Medicare following suit in the long term. Organizations that are proactive in developing solutions – ideally in collaboration with regulators and other partners – will be positioned for future success.

Working with a national provider organization to address the needs of diabetes patients, we focused on SDoH in determining how to shift the site of care to the home. Patients with mobility issues, those that lived in food deserts, or lacked reliable WiFi for remote diagnostics each required different design decisions. As innovation strategies more frequently intersect with regulatory requirements, we help clients think through the implications and find opportunities to streamline compliance processes as an outgrowth of experience design and technology development.

5. You can’t change your clinical care model without changing your business model.

This might be the hardest challenge in healthcare, because of the frequent tension between what’s good for patients and what’s good for the bottom line. In theory, clinical care organizations can find the financial backing to move to a more consumer-centric clinical care model in one of two ways:

- Improving patient loyalty and outcomes to become a recognized market leader or provider of choice, with the net effect of boosting both patient volumes and financial returns.

- Maximizing reimbursement for all kinds of clinical care services including those delivered outside the traditional clinic.

We’ve found the first is a harder recipe for success and following it can lead to internal disbelief at best and barriers at worst. Financial incentives need to align with care incentives. Organizations that invest in transforming their care model should expect to realize financial rewards or at least figure out how to get paid for providing services that benefit patients.

To make it happen, we have helped strong leaders think outside of existing markets to create new categories of care based on patient needs. To model the potential for a new home health business that a diversified healthcare giant was launching, we created a consensus view of existing service lines that could be brought together to meet patient needs in the home, from infusions, to telehealth, to diagnostics and monitoring. Here again, the key was getting stakeholders to collaborate and communicate in new ways.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Is there a more human-centric industry than healthcare? With technology becoming ubiquitous in all forms of care delivery, it may seem an odd time to ask the question. But in our experience, healthcare organizations that master the human touch in both care delivery and designing and implementing their own transformation initiatives realize the best clinical and business outcomes.